Walking Book Club: Autumn 2025

In the late 1980s, I lived in Jefferson, NH, where I worked with an arsonist at the local family restaurant. Now before you get the wrong idea, I didn’t know he was an arsonist at the time. Heck, I sometimes wonder if even he knew, as he was a few sandwiches short of a picnic. The actual infernal mastermind of the fires was the owner of one of two gas stations in town, who could often be seen sweeping microscopic pieces of fluff from the tarmac in front of his convenience store while wearing a pair of vintage Mickey Mouse ears.

An Arsonist’s Guide to Writers’ Homes in New England achieved a similar ridiculous level of satire, except the book, thank goodness, was fictional. All of the targeted authors’ homes, to my knowledge, are still standing. I used to bike past The Frost Place Museum and Poetry Center in high school. I can tell you that aside from one brief road containing a string of a dozen mobile homes, the town of Franconia is nothing like the book’s embellished community for exiled alcoholic rednecks. And my kids would disagree with the author’s portrayal of Amherst and its farmer’s market, which is today a lively, organized weekend establishment on the newly-renovated town common. Nevertheless, Brock Clarke’s chimerical tour of a handful of stereotypical New England locations was amusing, weaving ludicrous caricatures of the main character’s family members and their peculiar antics (dinner with the main character’s soon to be ex in-laws was probably my favorite scene).

There is nothing so quintessentially New England as an autumn walk in the woods. With the waning fallen foliage crunching beneath our feet on a crisp blue sky afternoon, a few devoted readers ventured onto the two mile trail at the WLCT’s Dunham’s Brook Conservation Area. Over the boardwalk, up the hill, left at the steps, through the field, back into the woods. A pause at the fork to contemplate.

Clarke’s book was an unexpected mystery, with twists and turns and red herrings, but also with the kind of extensive character development that had you both rooting for and despising many members of the eccentric cast. Its unconventional theme caused readers to ask questions unrelated to the plot. Why do we preserve the homes of so many authors? What do these locations tell us beyond what’s already written on the page?

“Where was the poet to tell me what to do when the door to the road less traveled was locked?” (p.168)

We long to feel connected to authors of stories we have read, especially those that were meaningful or whose characters worked themselves into our memories. What questions would we ask them if we could? We expect New England’s people, landscape, and even its authors to conform to certain stereotypes. We visit these landmarks to admire specific period architecture or identify symbols of a regional identity unique to colonial America.

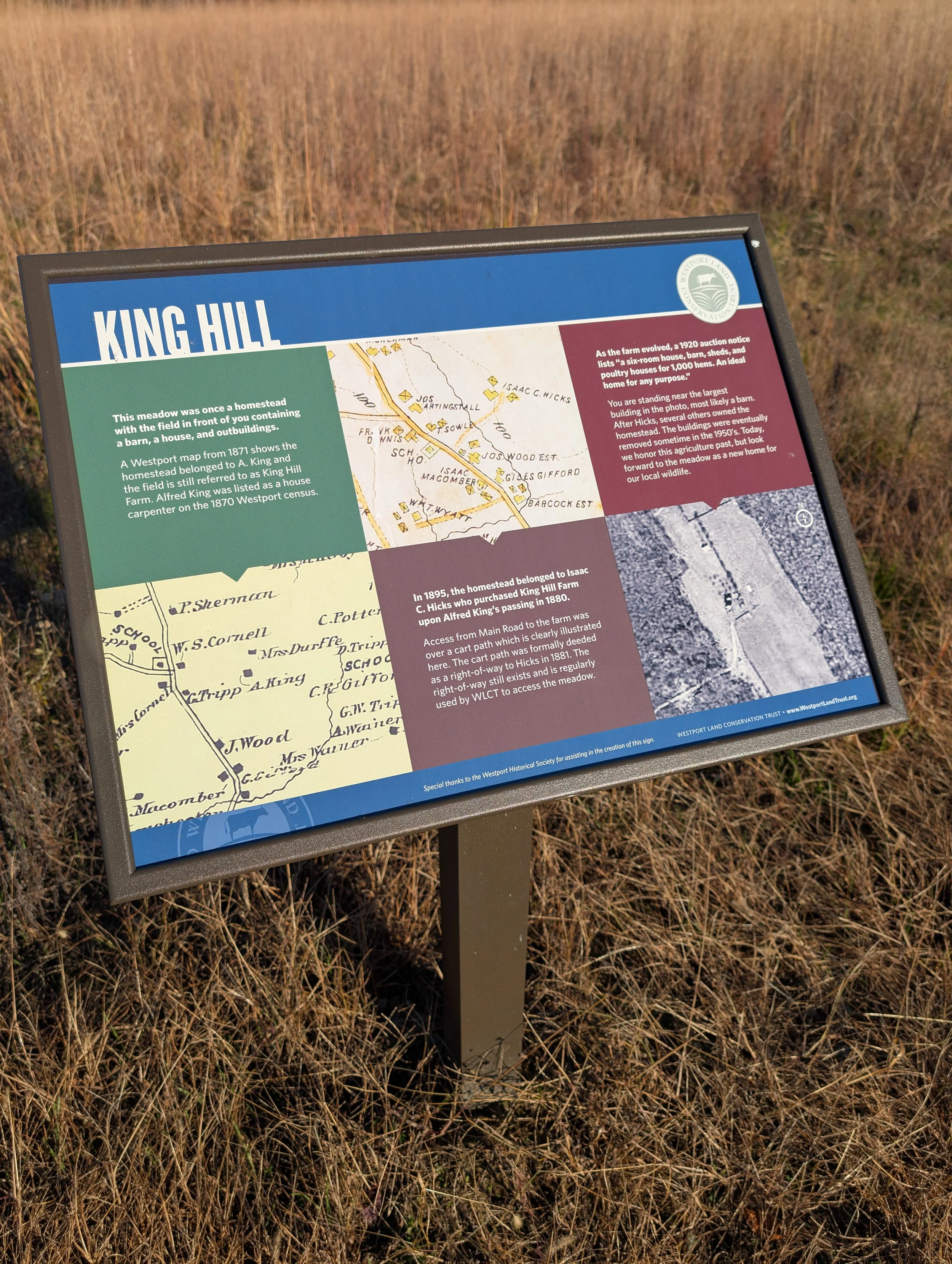

The 88 acre property of Dunham’s Brook is a lovely example of rustic New England charm. A recently added placard in the broad meadow describes some of the previous owners of the homestead of what used to be known as King Hill. The farm was purchased by Isaac Cook Hicks (1853-1928) in 1880 after the passing of the former owner, carpenter Alfred King.

Isaac C. Hicks and I are very distant cousins (his great (x6) grandfather and my great (x11) grandfather was James Thomas Hicks, married to Phoebe Allyne in England in 1578). Some of the Hicks family who migrated to the Massachusetts Bay Colony changed the spelling of their last names to Hix, hence locations such as Hix Bridge Road which crosses the east branch of the Westport River. It is connections like these that many of us take delight in learning, for no other reason than they make us feel like a part of an area’s future history. As a writer, they spark the desire to create local stories of historical fiction.

When we walk into an historic author’s house (or replica of, due to fire, not usually arson) such as Thoreau’s tiny cabin at Walden Pond, we may be looking for insight into the author’s mind. We try to imagine what enlightened him, just as we might try to envision the stories of those who worked the land of King Hill in centuries past.

The homes of Emily Dickinson, Robert Frost, Herman Melville, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Edith Wharton, Edward Bellamy, and of course, Henry David Thoreau were all mentioned or played pivotal roles in Clarke’s madcap mystery. Surprisingly, other authors were omitted, such as Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Louisa May Alcott, Harriet Beecher Stowe, or Sylvia Plath. Some authors such as W.E.B. DuBois and Edgar Allan Poe have no surviving buildings to visit, so it’s up to writers and artists to invite others into their imagined private worlds. Stephen King and other currently living authors probably don’t want tourists descending on their homes no matter the intentions of their fans.

Arson is a crime looking for attention. Besides the string of homes set on fire in northern New Hampshire that I was witness to, the most well-known in the area was the 1982 Boston arson spree, which included 160+ fires set as protests to police and firefighter layoffs. While there are plenty of fictional stories about arson, there are few non-fiction titles, but they include the informative Fire Lover by Joseph Wambaugh and The Library Book by Susan Orlean. As for me, I’m adding a few titles mentioned in Clarke's book to my reading list, such as Looking Backward by Edward Bellamy and Ethan Frome by Edith Wharton.

An Arsonist’s Guide to Writers’ Homes in New England stirred up more questions about New England cliches and the nature of family relationships than any interesting conversations about the plot of the book itself. Sam Pulsifer, the book’s accidental arsonist, certainly didn’t elicit an urge to go increase my home’s fire insurance coverage.

The most famous landmarks in Westport, such as the memorials for Paul Cuffe and the Handy House, are both thankfully in close proximity to the fire department! I’d give this creative piece of fiction a solid 3 out of 5 stars.

Join us February 15, 2026 at 2pm for a winter walk at Gooseberry Island while we discuss The Mermaid of Black Conch, by Monique Roffey.